distress caused by Marie-Thérèse’s accidents prompted Picasso’s turn to votive magic: ex-votos — vows to gods, be they Mithraic or Christian — in the face of sickness, accident, or death. A sequence of votive works, paintings as well as sculptures, would dominate Picasso’s imagery for the next four months and reappear sporadically over the next four years.” Similarly Widmaier Picasso responded to her own question concerning the raison d’être behind the many Rescue paintings, drawings and etchings produced between November 1932 and January 1933, by saying, “Are they votive offerings or symbols of a resurrection?” (Widmaier Picasso 2011: 210). Cowling has also described certain Picasso portraits of Marie-Thérèse as having talismanic properties, in which case the transition from a protective act to a celebration or commemoration of a perceived act of divine intervention in the form of an ex-voto is a natural progression (Cowling 2002: 532).

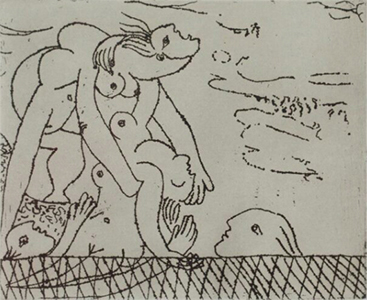

In one of The Rescue paintings a bearded nude male figure is shown rescuing Marie-Thérèse, possibly Picasso himself in the guise of Nereus the sea deity personified as ‘the old man of the sea’. He was father to the Nereid sea nymphs and everal of the rescue scenes depict water-nymphs engaged in rescuing Marie-Thérèse (Fig.20-21). One wonders if the Nereus reference is also an oblique homage to one of his favourite painters Jean-Auguste Dominique Ingres and his epic work Jupiter and Thetis (1811). Although involving a slightly different cast of characters it too involves a rescue theme in which Thetis, Nereus’s daughter, pleads with Jupiter to save Achilles. Jupiter, like the male figure in Picasso’s painting, is depicted partially nude and heavily bearded. The thought of being both Nereus and Jupiter, especially as personified by Ingres, would have appealed to Picasso.

The Rescue series was not the first time that he attempted to associate his art with divine intervention designed to privilege life over death. When his young sister Conchita lay dying of diphtheria he tried to bargain with fate by vowing that he would never paint again if his sister’s life was spared (Richardson 1992: 49). Some 50 years later he reiterated this life affirming position with the words that he used to conclude his speech at the 1950 Communist sponsored Peace Congress, in Sheffield, “I stand for life against death; I stand for peace against war.” (Penrose 1962: 329).

On the first page of her 2022 publication Marie Thérèse-Walter and Pablo Picasso : biographie d’une relatio Laurence Madeline attempts to cast doubt on the very premise that the Rescue paintings are linked to a swimming or kayaking incident that occurred in 1932. She does so in order to pursue the legitimate proposition that some art historians prefer to contextualise using anecdotal “legends” rather than settle for more mundane artistic contexts. By way of an example she cites the Rescue series of paintings that many writers see as predicated on the 1932 river Marne incident and then she attempts to undermine their theses by referring to one of Lydia Gasman’s notes from her 1972 interview with Marie Thérèse-Walter, which reads, “[1934] she was seriously ill [ didn’t say where she was...". My copy of this note, kindly provided by the Lydia Gasman Archive, reveals that it was probably written after the interview took place because it is prefaced by “she said [ but I am not sure she remembers accurately…” Perhaps she was also ill in 1934, but no other source, family or otherwise, has provided corroborating evidence. In contrast, Marie Thérèse’s sister ( a medical practitioner) and daughter Maya both described the Marne incident and resulting illness as taking place in 1932. Diana Widmaier Picasso's essay in "Rescue: The End of a Year" (in Picasso 1932, Love Fame Tragedy, Tate Publishing, pp.208-233), confirms the 1932 date and provides an in depth analysis of the Rescue series of paintings, etchings and drawings.

21

21Fig. 20 Picasso. The Rescue (Bearded man), painting, 1932

Fig. 21 Picasso. The Rescue of the Drowned, etching, 1932