Une Anatomie, Minotaure and Surrealism

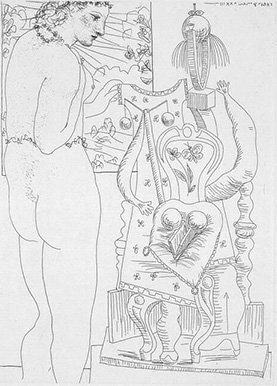

The Rescue theme that precedes the Une Anatomie drawings and the celebration of his muse’s return to health in the etchings help contextualise the Une Anatomie drawings as ex-voto representations of her illness inspired by trauma and pent-up desire. But they do not resolve questions concerning their dramatic stylistic difference to the themes that surround them. Simply describing the anatomy drawings as skeletal figures or “conceptual sculptures” does not do justice to the many surrealist visual tropes that underpin the drawings and their references to African tribal art, also part of the Surrealist creed. But why surrealist? Picasso was certainly an eclectic artist, but he resisted any attempt to classify him as part of any group that he was not the instigator of. On the other hand he naturally subscribed to many of their beliefs, particularly those that advocated that creativity should be predicated on anti-logic, dreams, magic and mysticism, rather than empiricism. And most important of all that the so-called tibal “savage” and “primitive” mind should take precedence over intellectualised reason. It is well documented that the primary innovators of surrealism tried to use his established reputation to further their credibility and at the same time the movement’s popularity. The invitation to be the featured artist in Minotaure’s inaugural issue and to create its first cover is an obvious example of the group’s attempts to bring him into the fold. Picasso’s response was to offer them Une Anatomie, which personifies the surrealist belief in the doctrine of “objective chance”, inspired by the now infamous line in the Comte de Lautréamont’s Les Chants de Maldoror, “It is as beautiful as … the chance encounter on a dissection table of a sewing machine and an umbrella!” At the same time it gave him the opportunity to have his ex-votos reproduce many times over, which to a superstitious mind such as Picasso’s, would have made them increasingly powerful.*

No doubt the magazines name appealed to him because he personally identified with the mythical creature whose man-bull persona enabled him to express the full range of human and animal emotions in a single character. At the same time it was also a surrealist trope that was emblematic of forbidden desires. In addition to indulging his fascination for the minotaur Picasso used the magazine to bring his recent sculptural work to public attention, particularly the large

* For more on Picasso’s relationship to Surrealism see “In Surrealist Company 1924-1934”, Cowling 2002: 452-552

32

32