The following text expands on the mainly intuitive decisions that shaped the transcribing process that began in the 1990s and also discusses the subsequent research carried out in the intervening years, much of which has revealed that many of the early intuitive responses to the drawings were more revealing than at first realised. And for this I would like to thank the many Picasso scholars and biographers that are cited throughout the following text. Soon after the three-dimensional versions were produced they were exhibited in the Freud Museum, London in 1999, in an exhibition titled BURIAL curated by the then director Erica Davies with an introductory text by the art historian and critic Graham Coulter-Smith.* During the planning for the exhibition I intuitively decided to exhibit the Une Anatomie bronzes with an assortment of female cosmetic items. This seemingly bizarre juxtaposition was motivated by a desire to give life back to these figures, which I had, from the outset, always thought of as skeletal women in search of a life giving force.

In Search of the Encoded Secret

During the early years in which Picasso guarded his private life and commentators on his work initially respected it, the art world was content to discuss his oeuvre in polysemic terms. However, as more personal information emerged the temptation to analyse his work against a backdrop of biographical detail became irresistible. Those who cautioned against this approach where soon in the minority largely because Picasso’s habit of meticulously dating everything provided the perfect opportunity to align his art with emerging biographical details. The Picasso scholar and biographer John Richardson was the first to describe the anatomy drawings as "conceptual sculptures” depicting his then muse Marie-Thérèse Walter in the form of “pinheaded female figures” (Richardson 2021: 19; 2007: 488). This view is supported by Elizabeth Cowling’s observation that, “Picasso’s love affair with Marie-Thérèse Walter coincided with one of his most fertile periods as a sculptor. Her face and body aroused the irresistible urge to sculpt in a powerfully volumetric style and inspired works ranging from the relative naturalism of recognisable portraits to extreme biomorphic abstraction in which her defining traits can barely be detected.” (Cowling 2011: 257). The fact that Marie-Thérèse was Picasso’s muse when the drawings were produced adds credence to Richardson’s observation, which is made even more credible by the fact that these abstracted figures have female attributes characterised by vaginas masquerading as folded baskets or V-shaped water-channels.

3

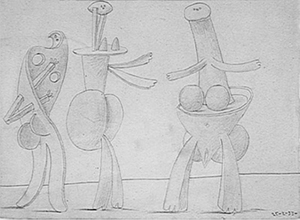

3Fig.3 Picasso. Une Anatomie: two women and an androgynous ithyphallic male, drawing, 25-2-1933

Fig.4 Owen. Androgynous Ithyphallic Male, bronze, 1995, after Fig.3

4

4 Balls are also sometimes suspended on cords so that they ambiguously signify either breasts or buttocks. These quasi-human forms are held together by furniture-like armatures made up of shapes that resemble tables and chairs, all of which gives the figures a surrealist skeletal-like appearance. The theory that all these figures are modelled on Marie-Thérèse is somewhat challenged by the fact that amongst the group is a figure resembling a penis on legs, whose erection resembles an ancient ithyphallic demigod, similar to those found on ancient Greek vases and Roman talismanic sculptures. Even more mysteriously this phallic figure appears to be androgynous because it also has a vagina (Figs. 3-4). Whilst the image of the hermaphrodite is not uncommon in the history of painting and sculpture, it is rare that a figure is depicted with both male and female genitalia. Since Picasso was never arbitrary in his use of imagery this sexual juxtaposition may well be the key to unlocking these drawings.