The 400 pages that Gasman devoted to unpacking the significance of the “cabana” or beach hut and its unlocking by malevolent or benign women, cannot be fully acknowledged here and is best, therefore, summed up by her own words, “the Cabana Series is a symbol of Picasso himself and stands for his alienation from a malevolent external ‘Mystery’ that is paradoxically immanent in his own psyche.” (Gasman 1981: introduction).

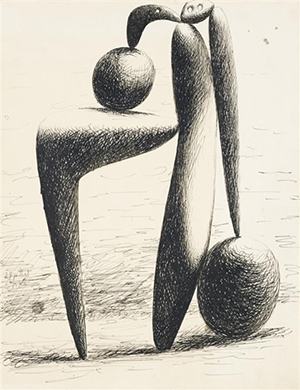

During his 1928 Dinard beach holiday that secretly included his muse, he created sketchbooks that once again contained numerous depictions of increasingly sculptural figures, but this time they were made up of an assortment of pebble and bone-like shapes (Fig.12). According to John Golding the Dinard pebble and bone figures pre-figure the Une Anatomie series in terms of assemblage or skeletal structures (Golding 1973: 101). These sketchbooks clearly demonstrate that Marie-Thérèse ignited his desire to create sculpture at a time when he did not have a sculpture studio and he, therefore, used virtual techniques to personify her and his desire for her. After purchasing Boisgeloup, an 18th-Century French Château near Paris in 1930, his sculptural depictions of Marie-Thérèse no longer remained virtual and her distinct features began to appear in the form of numerous portrait heads. The monumental sculptural gravitas expressed in these heads confirm that he first and foremost perceived his muse in physical and therefore sculptural terms. George Brassaï’s photos of these heads featured in the inaugural issue of Minotaure along side Picasso’s Une Anatomie drawings, which depicted an altogether different sculptural view of Marie-Thérèse.

Une Anatomie and Family on the Beach

No oversized key appears in the beach hut door depicted in Une Anatomie’s title page, which was produced four days before the first of the Une Anatomie drawings (Fig.13). However, the presence of a reclining male, a child and a fecund archaic goddess-like figure gives pause for thought. The woman’s fulsome form is a stark contrast to the skeletal female forms that follow and is also unlike the sexually active femme phallus or ithyphallic women in Picasso’s 1927 and 1928 sketchbooks. Neither is she like his wife Olga, the frail ex-ballerina. On the other hand she is like the Venus of Lespugue, the archaic fertility goddess that Picasso was known to have copies of (Fig. 14). 12

12