During those fifty years the ‘isms’ of Modernism (Surrealism, German New Realism, American Expressionism, Minimalism and Conceptualism) came and went, until eventually the relentless reductive processes associated with Modernism reached their inevitable and finite conclusion – silence, a blank canvas and a sculpture indistinguishable from the floor. A quantum leap was called for, a deus ex machina that could extricate twentieth century art from its tragic silence (some would say its impotence) and hence the eighty-two years old enfant terrible once again reemerged onto the world stage, along with the movement he unwittingly helped to create, which became known as Postmodernism. And thus De Chirico was twice born. Like Dionysus he was plucked from Hades grip and in his case he was clutching a prolific crop of new paintings. To the emerging generation of young Postmodernist painters he offered a ready-made paradigmatic shift. They were a generation who wanted to paint and not talk about painting. The old values became the new values and the craft of painting and its iconographic syntax – metaphor, illusion and allusion – were rehabilitated into the armoury of the ‘New Painting’.

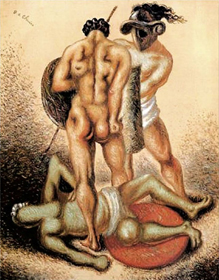

Unlike his later paintings, the works De Chirico produced between the years 1910 to 1920 were internationally acclaimed. The features that set them apart from other paintings consisted of a disquieting sense of irreality and a dislocated logic, normally associated with dreams. At the turn of the twentieth century various Paris-based artists such as Dali, Tanguy and Ernst, and the Surrealist poet and theoretician André Breton quickly realised their poetic and psychological potential. So too did René Magritte in Belgium, along with the German Neue Sachlichkeit artists Georg Grosz, Max Beckmann, Otto Dix and Oskar Schlemmer. The paintings that represented a point of departure for these artists fall into three main groups: the Italian Piazzas from 1910 onwards, the Mannequins from 1914 onwards and the Metaphysical Interiors from about 1916 onwards. Collectively they form the visual text for De Chirico’s metaphysical landscape (fig.1-3). The so-called Classical Mannerist paintings that brought about his downfall, first at the hands of the Surrealists and subsequently at the hands of certain institutions and critics, date from the 1920s onwards (fig.4). In retrospect it is now clear that both his metaphysical and classical paintings remained consistent features of his work until his death in 1978.

Contrary to popular belief De Chirico did not die in the 1920s. The reason he did not go on to receive the accolade he deserved was only partially due to the critical attack led by the Surrealists. Curators at certain major international museums and galleries also attempted to suppress the showing of his later neo-classical paintings. Picasso, to a lesser extent, also fell victim to the same cultural Mafiosi , who took it upon themselves to become judge and jury over his later paintings. Only in the 1980s was that part of Picasso’s and De Chirico’s oeuvre allowed back from the cultural Gulag, at the instigation of certain enlightened curators such Gérard Régnier at the Musé e National D’Art Moderne, Paris. De Chirico, I suspect, is still too bitter a pill to swallow for those curators who would rather hang a hundred snowballs on their gallery walls than one late De Chirico.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

41. Giorgio de Chirico The Red Tower 1913

2. Giorgio de Chirico The Prophet 1915

3. Giorgio de Chirico Metaphysical Interior 1916

4. Giorgio de Chirico The Gladiators 1928