1

1Fellini uses the silent film reconstruction within Roma to satirise earlier political and religious clichés. His juxtaposition of on and off-screen religiosity, pointedly reveals and undermines the way in which early Italian film blatantly promoted Catholicism. In contrast, the spoof Fascist propaganda film satirises Fascist attempts to exhort Italian youth to engage in gymnastic exercises in order to fight for the motherland (fig.1). A blaring voice over extols them to become strong like their glorious Roman forbears who conquered Hannibal and Carthage. Ironically these are the same 'pagan' forbears who fed Christians to the lions. The propagandist agendas initiated in black and white by Rome’s Cinecittá, were latter transformed by Hollywood into Wide-Screen Technicolor extravaganzas. It too based many of its film scripts on novels containing equally bogus Christian persecution plots to produce movies such Quo Vadis? (1951) (fig.2), Nero or the Fall of Rome (1909), The Sign of the Cross (1932), Sins of Rome (1953) (fig.5) and Ben Hur, (1959). These films turned romanticised Christian martyrdom into a box office success by tapping into America religious fundamentalism and the insatiable global desire to witness spectacular versions of history.

Swords, Sandals, Togas – the problem of authenticity

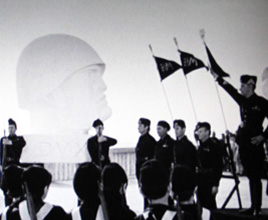

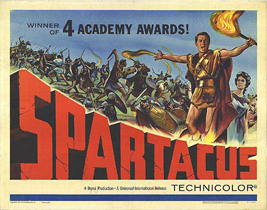

From the earliest days of cinema to its Hollywood incarnation film producers made extravagant claims concerning authenticity. It was as if the moving image was destined to make history ‘come alive’ and ‘tell the greatest story ever told’. Hence, claims regarding historical authenticity were very much at the forefront of publicity campaigns. Lavishly expensive films, or toga movies as they were cynically called, such as Cleopatra (1963), Cleopatra's Daughter (fig.3), The Fall of the Roman Empire (1964) (fig.4) and Spartacus (1960) (fig.6), as well as low budget B movies featuring the latest Mr. Universe (fig.7), all made preposterous claims concerning authenticity and the amount of money that was required to achieve it. Most were in fact made in Hollywood studios or on the dunes of California and despite the purportedly large sums spent on them and the availability of large amounts of historical evidence, the film sets were invariably caricatures derived from nineteenth-century paintings. Toga movies such as Quo Vadis? revelled in contrasting Christian piety with pagan hedonism, supposedly signified by absurdly overstated film sets made up of copious amounts of faux gold, marble and wall-paintings. The Satyricon, an ancient satirical text thought to have been written by Petronius, Nero’s arbiter of taste, provided the basis for many of the hedonistic storylines and lavishly excessive sets. History seen through the filter of fantasy and spectacle, rather than authenticity, often determined the choice and positioning of most of the historical mise-en-scène references.

1

1 3

3 5

5 4

4 6

6 7

7

|