1>

1>Agathodaimon – serpents, snakes and other forms of eschatological imagery

So powerful was the need to make the house resemble a sanctuary that the already potent cocktail of Lares, Penates and Genii was eclipsed by an even more prolific guardian and fertility symbol that took the form of a snake (figs.1-3). Whilst not representing an identifiable species, the agathodaimon or good-luck snake appears similar to a constricting serpent. Its ghost-like capacity to shed its skin and its elusive presence above and below ground made it the most reproduced of all the household spirits. In Pompeii agathodaimon are usually represented as male and female pairs approaching an altar on which offerings such as an egg, pinecone or pomegranate are placed. These offerings as signifiers of birth and fecundity and collectively symbolise rebirth (fig.4).

Offerings such as these symbolised primal regenerative matter awaiting fertilisation by the serpent’s iconic sperm. They appear in many auspicious contexts, on the walls of tombs and sarcophagi, on talismanic sculptures and as finials on the top of tomb monuments, signifying rebirth and immortality. Snakes, along with other animal, bird and plant motifs, were an important part of ancient eschatological symbolism associated with sarcophagi and burial chambers (fig.5). Snake images were also attributed with apotropaic powers and hence used to prevent evil entering the house. Some depictions of snakes are accompanied by texts that warn against more mundane perils such as inappropriate urinating, defecating or making bad smells within the house. Like the lares and penates, serpent/snake worship is thought to have originated in ancient agrarian beliefs that sought protection and a good harvest from the mysterious creature that emerged from and disappeared back into the underworld. In so doing it also came to signify the returning spirits of deceased ancestors and as such became a ubiquitous funerary image as well as one associated with domestic shrines (fig.6).

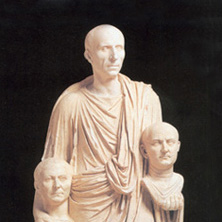

The ancient practice of in-house burial may have initiated ancestor worship within the house and conversely the proliferation of ancestor cult images, such as imagines and sculptural effigies, could well have been given an incentive by the edict of the Laws of the Twelve Tables, which banned the burial of human remains within the house and city walls, thus creating the need for symbolic substitutes (fig.7).

7

7

|