The Railway Architect

Earlier in this article I quoted Grenier, who informed us that the Manes (or Shades of the Dead) emanated through the spirit of the Father, the ancestral head of the Roman family. His genius loci was often visualised as a serpent emerging from the earth in order to taste the offerings placed in the family hearth. De Chirico’s genius loci, his father, was a railway architect and this is the point at which he enters the mystery. It is my underlying thesis that throughout his working life as a painter, De Chirico attempted to conjure up the ancient spirit world of his own ancestors, and in particular the spirit of his father. What is truly remarkable and mysterious is that he did it in a pictorial form that closely resembled that developed by his fellow countrymen nearly two millennia before him, and in a pictorial form that it seems he was not aware of and in many instances could not have been aware of, due to the strange occurrence that post-dates it – the volcano.

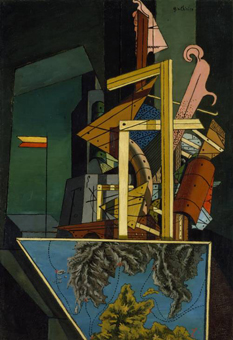

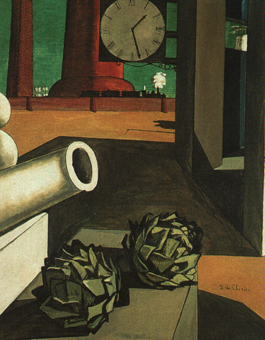

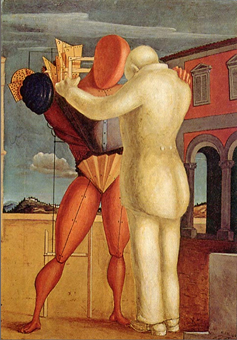

The ancestor spirit most obviously implicit in his paintings is his father. The various train motifs, literally hundreds, which melancholically traverse the landscape beyond the wall, along with numerous references to technical drawing paraphernalia, attest to this fact (figs.1-2)). Picasso once referred to him as the “painter of railway stations”. His father’s premature death had a profound effect upon the young De Chirico. In his memoirs he describes the moment of realisation that his father had died, the sense of loss is vividly expressed in the following quote: “It was May and a most beautiful day in the city of Minerva. All at once, on my right, on the other side of the street, I saw on the first floor balcony of a house a great black pall flying in the wind. It was like a flash of darkness in the bright light that flooded everything. I felt a sudden anguish and a terrible presentiment. I felt that something fatal had happened at the house I had left. I quickly turned round and went home. When I arrived I found the main door wide open and saw that someone had gone out in a hurry. I hurried towards my father’s bedroom. On the stairs I met Don Brindisi who embraced me and tried to take me downstairs again to the ground floor. I broke free and ran again towards my father’s bedroom. When I entered I saw first my mother and my brother sobbing. I rushed over to the bed where my father was lying: he looked tranquil, with his eyes closed and a serene, almost happy expression like someone who, tired after a long and exhausting journey, was at last resting in sweet and deep sleep”. The image of De Chirico’s father is also embodied in the Return of the Prodigal Son series (figs.3-4)). He is evoked by the statuesque figure seen from the rear wearing a frock coat denoting a nineteenth century gentleman. The son that he is embracing is presumably De Chirico, who has taken on the mantle of his father’s profession; he has become a mannequin composed of geometric symbols reminiscent of the tools of the railway architect – he has become a spatial Argonaut.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4