1>

1>In many respects the physical and conceptual synthesis of real and virtual space is at the heart of Roman visual culture. The dialectic balance it created between exterior and interior forms created highly functional, and at the same time highly symbolic spaces, many of which have had an enormous global influence. The Pantheon in Rome is a primary example. Domestically located wall-painting reversed the exterior – interior polarity at the heart of Roman architecture and augmented physical spaces with virtual space. It is easy to lose site of the dialectical relationship that wall-painting created between actual interiors and virtual exteriors, because so many of them are now separated from their original locations and groupings. And in some cases they only exist as illustrations in books.

Trompe l’oeil

The numerous juxtapositions of trompe l’oeil architecture, nature and mythology uncovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum were not cheap substitutes for the real world. They presented the viewer with an entrance into a meta-world made up of illusions, allusions, signs, symbols and metaphors. Architecture, by its very nature, is grounded by physical principles, but trompe l’oeil depictions of architecture can exist in any number of worlds governed only by the imagination (fig.1).

The ubiquitous presence of trompe l’oeil techniques in Roman wall-painting is often linked to a desire to psychologically enlarge room dimensions. Whilst this may have occurred, citing it as a primary raison d’être does not explain why some of the most sophisticated examples of trompe l’oeil have been found in very large rooms, such as in the atrium of the Villa di Poppea (fig.2). In the case of this particular villa its surrounding seascape and landscape also provided it with superb views, so there was no need to compensate for this by creating pictorial vistas. Using pictorial space to psychologically enlarge small windowless rooms seems logical, but the visual evidence runs counter to this logic. The majority of small rooms were used as bedrooms, amongst other things, and many were found painted in faux marble, or planar architectural facades, or a ground colour with floral motifs, all of which emphasised the solidity of the wall (fig.3). Paradoxically, as spatial illusion became more and more prevalent, artists still continued to define the boundaries of the room by creating simulacra walls and faux architectural features.

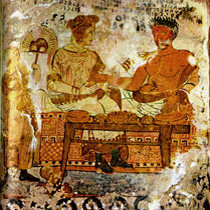

The primary characteristic that sets Roman wall-painting apart from either Egyptian, Etruscan or Greek, is that it consistently redefines the 3-dimensional space in which the compositions are created. In the majority of cases it did this by incorporating the architectonic features of the room into the pictorial composition. Egyptian wall-painting, in stark contrast, was planar and diagrammatic and made virtually no spatial reference to either the room or chamber in which it was created. Etruscan wall-painting, characterized by those found in Tarquinian tombs in Italy, used similar planar characteristics combined with a greater degree of natural figuration (fig. 4).

1 Panel from a much larger wall-painting – Palaestra, Herculaneum (Museo Nazionale Archeologico di Napoli), which may have influenced 19th-C. Theatre

2 Large Atrium – Villa di Poppea, Oplontis

3 Casa delle Nozze d'Argento, Pompeii

4 Tomb of the Shields, Tarquinia, Italy

4

4

|