1>

1>Four Styles: difference versus synergy

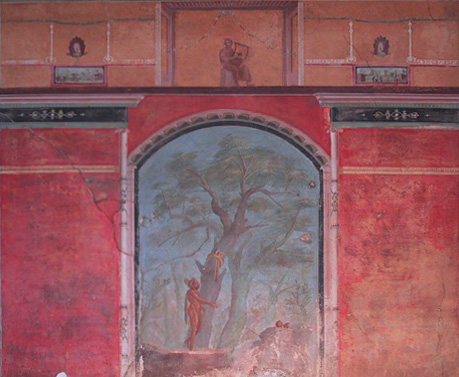

Whilst Mau's and subsequent studies are valuable from a purely formal perspective, they actually tell us virtually nothing about the semiotics and semantics of Roman wall-painting. In fact quite the contrary, the search for ever more subtle stylistic ‘difference’ caused the ‘Four’ styles to become increasingly polarised. As a result, iconographic and teleological similarities that transcend the four style division are invariably ignored. Such as, for example, the frequent use of aediculae (shrines) or votive imagery that is often in the form of commemorative offerings. All of which consistently appear in styles two, three and four and are seldom credited with having symbolic value (fig.1). This lack of iconological analysis was partially due to overly formal analytical methodologies and partially due to the ‘decorative’ classification that was attributed to the paintings soon after their discovery. Hence, the aedicula form, which is often literally and metaphorically central to the wall-paintings, no longer signified its original meaning. Instead, it was relegated to a purely decorative function along with numerous other religious and ritualistic motifs such as gods, heroes, victories, satyrs, Nikes, maenads, tholoi (circular shrines), and imagines clipeatae (commemorative shields). There largely decorative classification also appears to have stopped informed readings of the imagery within compositions. For example, the 'magic' fruit that Hercules was sent to retrieve from the garden of Hesperides is invariably described as 'golden apples' and yet the fruit depicted in fig. 2 (and many other wall-paintings) is quite clearly a pomegranate. Given this fruits pre-Christian symbolism relating to betrothal, the underworld and immortality, it makes it far more likely that the life-giving 'golden apples' in Hera's garden were in fact pomegranates (Fig.2).

Although nineteen hundred years separate the interiors of Pompeii and the copies that proliferated throughout modern Europe, Mau applied the same critical position to both. Ironically, even though he wrote extensively about all aspects of Pompeii, it was his formal analysis of the wall-paintings that he is best remembered for. It is now virtually impossible to discuss Roman wall-painting without reference to his four style classification. The fact that his theories remain unchallenged, does not mean that we should also accept his aesthetic analysis of the wall-paintings, which was inherently flawed for the following reasons.

Despite the fact that he had daily contact with the wall-paintings over many years, his critique of them demonstrates that he had no hesitation in judging them by his own aesthetic criteria and that of his age. Mau, like most of his contemporaries, evaluated Roman art using ancient literary references to Greek art and his own sense of good and bad taste. All the following quotes are taken from Pompeii: its Life and Art (1899): “….the decline of taste due to the long and terrible war are unmistakable.” (42); “The whole arrangement is in excellent taste, while the execution is careful and delicate.” (97); "...one of the decorators had a fondness for representing mythological scenes by moonlight, manifesting a taste little short of barbarous.” (322); “The complex designs and brilliant colours form a decorative scheme which is often most effective, although the system of the third style reveals a finer and more correct taste.” (460).

2

2

|