1

1Mau and the identification of pictorial subject matter

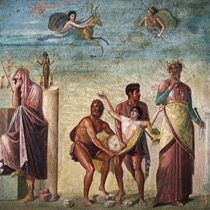

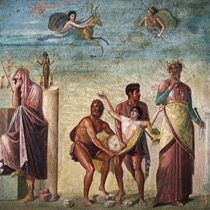

Mau only attributed 'subject matter' to picture-like compositions within the wall-paintings. These had to be either architecturally framed or figurative compositions on decorative and monochrome backgrounds. In other words compositions that resembled pictures hanging on walls. At the same time he attributed no significance to subject matter other than the type of aesthetic pleasure that accompanied picture viewing in his own age. This is clearly emphasised by the fact that he thought that the most ‘important pictures’ were the ‘mythological paintings’ (fig.1).

“It is by no means easy to make a satisfactory classification of Pompeian paintings according to subject. Nevertheless, with a few exceptions, they may be roughly grouped in four general classes, mythological paintings, genre paintings, landscapes, and still life. Most of the large and important pictures belong to the first class. The mythological paintings will therefore be discussed at somewhat greater length; the other three classes will require only a brief characterization.” (Mau 1899:464) (fig.2&3)

This quotation also reveals that he attributed no significance other than decoration to the pictorial frameworks surrounding the ‘pictures’. The fact that the entire room was a 3-dimensional painting appears to have eluded him and so it would seem, many other writers on the subject. The terminology that he used to identify subject matter not only dislocates it from the overall composition, but also mirrors the pictorial concerns of his own age. For example his use of the term ‘still-life’ painting, which he associates with Vitruvius’s references to xenion (fig.4)

"The still-life paintings represent all kinds of meat, fish, fowl, and fruits. According to Vitruvius, this kind of picture was called Xenion. The reason given for the name recalls a curious custom of ancient Greece. When a guest, xenos, was received into a Greek home, says this writer, he was invited to sit at the table for one day. After that provisions were furnished to him uncooked, and he prepared his own meals. A portion of unprepared victuals thus came to be called xenion, the stranger's portion, and the name was afterwards transferred to pictures in which such provisions appear.” (Mau 1899:464)

The irony here is that by describing them as ‘still-life’ paintings he equates them with a genre that became fashionable in early 17th-C. Holland, subsequently spread to the rest of Europe and was itself partially influenced by ancient Roman ‘still-life’ painting discovered in Rome in the 16th Century. Dutch painters such as Frans Snyders were probably introduced to them whilst studying in Rome in the early 1600s. (For more on this connection see Charles Sterling, 1981, Still Life Painting: From Antiquity to the Twentieth Century.)

In associating paintings of ‘meat, fish, fowl, and fruits’ with Vitruvius’s reference to xenion Mau set in trend a discourse that linked all such visual representations with ‘hospitality’ painting. And this may well be the case with regard to the depictions of this type of subject matter that are stand-alone vignettes. However, there are also other examples of compositions that similarly depict arrangements of ‘meat, fish, fowl, and fruits’, that are located in a context that suggests a different raison d’être. This type of ‘still-life’ painting is always located in front of doors or porticoes or some other entrance motif, which nearby contextualising imagery links to a divinity or an ancestor cult.

1

1

s |