1>

1>Perspective as Symbolic Form

Like White and Damisch, Mau was either disinterested or unaware of the possibility that perspective in Pompeian painting was underpinned by a symbolic order, which is not surprising because his Pompeian Four Style classification was almost entirely based upon purely formal characteristics. When similar spatial characteristics were found in paintings elsewhere in the Roman world, his Four Style classification became Roman, as opposed to simply Pompeian.

In essence, Mau separated the wall-paintings into four groups on the basis of the amount of linear perspective that was present in each composition. In so doing patterns began to emerge that appeared to form natural groups, which he referred to as ‘Styles’. In terms of spatial evolution they are unsystematic. In the context of Mau's theory the First Style is devoid of perspectival references whilst the Second makes such sophisticated use of it that in some instances it rivals Renaissance painting. The Third Style re-emphasised the picture plane whilst also adding a further spatial dimension by incorporating perspectival compositions in the form of figurative and landscape paintings inserted into architectonic frameworks. The fourth created a pluralistic 'style' based on a spatial dynamic derived from synthesising styles two and three. The erratic nature of the Styles and what this might mean in relation to broader cultural or symbolic contexts was never an issue for Mau, largely because he only regarded the inserted ‘paintings’ or vignettes as works of art, the rest of the composition he considered to be purely decorative.

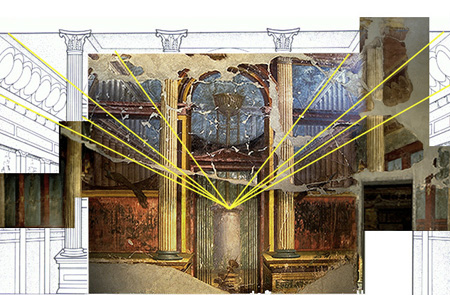

In relation to the history of art the Second Style is extremely significant because of its use of perspective at such an early date (fig.1). Following the collapse of the Roman Empire, Roman painting gradually went into decline and it was not until the Renaissance that comparable forms of perspective begin to re-emerge, by which time the earlier Second Style paintings had long since disappeared. When they were rediscovered in the eighteenth century their use of perspective was critically evaluated against costruzióne legittima, the geometrically rigorous techniques developed in the renaissance. Quite clearly Second Style wall-painting is not geometrically consistent, but this did not undermine its capacity to create convincing virtual worlds. In some ways their approach was even more sophisticated because they combined the psychology of expectation with perspectival techniques.

Their strategy was not unlike that of Parrhasius who used his competitor's expectations to win a competition to determine who was the greater artist. His rival Zeuxis may well have been the greater painter of verisimilitude, because birds tried to eat his depiction of grapes, but he lost the competition because Parrhasius tricked him into thinking that the pictorial curtains in front of his painting were real and thus Zeuxis asked for them to be removed. The Roman artists replaced the physical wall with its simulacra, thus creating a seamless transition to the virtual worlds that lay beyond it.

|