1

1

Our understanding of ancient Roman wall-painting is to a large extent shaped by its influence upon Neoclassicism, Romanticism and more recently twentieth century popular culture, mainly in the form of novels, films and television programmes. Hence the need to begin by reflecting on the artists, designers, novelists, librettists, composers, and film-makers, whose work has significantly affected the way we look at ancient Romano-Campanian painting, both within the context of their discovery and subsequent influence on, and then contamination by, the modern world.

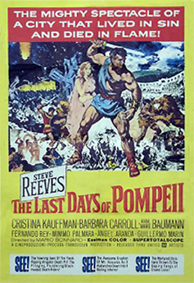

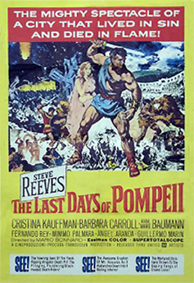

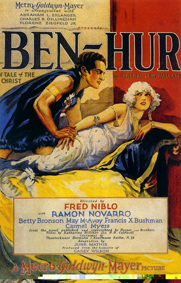

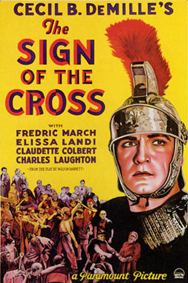

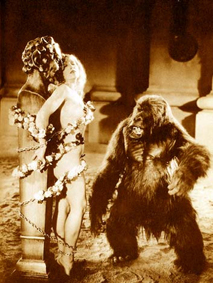

Most of the wall-paintings examined in this e-monograph date from approximately 150 BC to 79 AD, when the majority of the surviving examples were buried by volcanic debris. Post-discovery copies and appropriations have since merged with the original paintings and both now exist in a highly confused physical and conceptual space. As a result the ancient paintings are now only viewable through dense layers of subsequent cultural filters. These have accrued over many centuries as the result of socio-cultural constructions such as Christianity, the Italian Renaissance, the Enlightenment, Neoclassicism, Romanticism, and more recently Modernism and Postmodernism. In one way or another they all absorbed elements of Roman wall-painting and created their own ideological versions. The appropriated forms now influence the way that we view the 'originals' and no matter how much we try to discard them they remain distorting filters. For example, Hollywood toga movies from the 1930s onwards used decontextualised fragments of Roman wall-paintings to provide ‘authentic’ backdrops for their less than authentic portrayal of Roman society. Although often absurdly clichéd we still view the Roman world through the filters left by their juxtaposition of hedonism and savagely martyred Christians (figs.1-4). Hence, before we can study the ancient wall-paintings we need to be aware of the various factions and fictions that stand between us and the ancient material evidence.

Physically locating the ‘original material’ is itself a task fraught with difficulties, even though by definition wall-painting is site-specific. For various reasons, benign and otherwise, numerous wall-paintings were removed from their original locations, thus causing further decontextualisation. Paintings that were once site-specific are now viewed in touring exhibitions and wall-paintings that once formed narrative groups within a single room are now Continents apart. The Boscoreale villa of Publius Fannius Synistor is an example of this type of pictorial diaspora.

The wall-paintings that remain in situ are easier to narrative sequence, but their social context remains elusive because the objects and materials that once accompanied them have been removed or no longer exist. Hence, physically locating them can be as problematical as trying to determine the ideologies associated with them. The paucity of ancient texts concerning the paintings compounds the problems associated with their conceptual identity yet further. The lack of contemporary textual evidence and the dislocation of the paintings, created a conceptual vacuum that was rapidly filled by the numerous decorative, pictorial, literary, architectural and cinematic post-discovery appropriations, which became the filters through which Roman painting is now viewed.

1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4

|