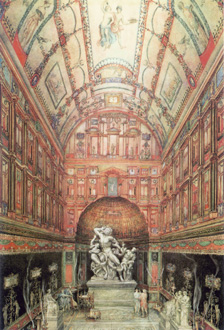

Unpacking the conceptual filters that stand between us and Roman wall-painting is unusually difficult because of the way in which it surfaced at such disparate points in time. For example, those discovered in Pompeii and Herculaneum emerged into a world already familiar with a reinvented type of Roman wall-painting, instigated by artists such as Ghirlandaio, Pinturicchio, Perugino, Filippino Lippi and Raphael. All of whom had ventured into the grotto-like spaces that were once part of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s Golden Place (fig.1). Raphael’s pastiche versions of Roman wall-painting were produced early in the sixteenth century for loggias and private apartments in the Vatican (fig.2). His designs were partially influenced by paintings found in Nero's palace and motifs taken from ancient coinage, architectural fragments, sarcophagi and pottery. His hybrid compositions echoed the ancient paintings, but were not consistent with their overarching compositional grammar.

When Johann Wolfgang von Goethe saw Raphael’s wall-paintings in the Vatican in 1786 he disparagingly described them as ‘frivolous arabesques’. (Goethe’s Italian Journey, diary entry for December 2, 1786, Penguin edition, p.147) His comment was made soon after visiting Michelangelo’s paintings in the Sistine Chapel and, as he himself later wrote, this may well have clouded his appreciation. Goethe’s displeasure on discovering that the great Raphael resorted to producing decorative pastiches, contrasts with the fact that the Papal elite of Roman society commissioned them precisely because they considered them to be ornamental and decorative. If they had contained the kind of significant meaning that Goethe desired their pagan origin would have made them unacceptable. The pseudo Roman wall-paintings that Raphael produced for the Vatican and later for the Villa Madama, soon became surrogates for the antique style, the only real examples of which still remained buried in subterranean grottoes (fig.3). The Papal Court used the Villa Madama to house visiting dignitaries and their entourage, including artist, and as a result copies of Raphael’s pastiché versions of Roman wall-paintings circulated throughout the Palaces and Mansions of Europe in advance of the wall-paintings discovered at Pompeii and Herculaneum.

When actual ancient wall-paintings emerged in significant numbers in the mid-eighteenth century in Pompeii, they came into a world that had already recreated its own pseudo versions of them. The aesthetic contamination was so significant that it became impossible to separate the original from the highly fashionable pastiché, which, somewhat ironically, became known as the Pompeian Style. The discovery of Pompeii and Herculaneum and their influence on contemporary design, accelerated the processes that divested the wall-paintings of their original symbolic meaning and made them indecipherable from the images they helped to create, such as those found in the pattern books of Robert Adam or Percier and Fontaine (fig.4).

1

1 4

4 3

3

|