1

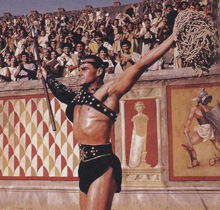

1The epic toga and disaster movies produced in Hollywood owe much to the early Italian silent movie versions of The Last Days of Pompeii, the first of which was screened in 1908. In the intervening years this theme has been remade at least five times, include a seven-hour TV adaptation made for ABC Television in 1984 (figs.1&2). Thus making it one of the most remade plots in film and television history. Lytton’s novel also gave rise to the lava saga, which pits human moral frailty against the terrifying forces of nature. Robert Harris’ Pompeii published in 2003 is a recent example. The book’s pre-publicity sensationalised the lives of the inhabitants who lived in the 'shadow of Vesuvius', by describing them as money obsessed hedonists, analogous to the dot-com billionaires who currently inhabit San Francisco’s Bay area. When cloaked in seemingly historical fact, inventions of this kind, whether they are Christian or pagan, invariably skew our perceptions of the ancient communities that they draw upon. Lytton's Last Days was not the first novel to use Pompeii as a dramatic background. Madame de Staël’s Corinne (1807) incorporated lengthy descriptions of the stricken city, which included bodies found in subterranean passage ways. One of them was a young girl who later became the inspiration for Théophile Gautier’s 1852 novella Arria Marcella: a memory of Pompeii (fig.3).

In comparison with much of the lurid material it ‘inspired’ Lytton’s unabridged original sometimes ‘appears’ quite scholarly. So much so that if one were to set aside its blatantly melodramatic content, it could in certain passages almost pass as a history book. As a result, fact and fiction merge and the barrier between reality and fantasy is blurred. History writing was a genre well known to Lytton who wrote a large tome on the History of Greece. In Last Days the historicising element is due to the unidentified third person narrator, who inserts what appears to be historical detail throughout the novel. Its “history book” appearance is also achieved via footnotes, a practice not normally associated with fiction writing. The majority of these have no bearing upon the plot but add authority to the text. In addition to historical interjections the unidentified narrator expands upon polemical obsessions that appear to echo Lytton’s own views on politics, religion, the supernatural and the advancement of English aristocratic values. On many occasions his class predilections and his dandyism are fore grounded in surprising ways. In the following quote, the narrator simply refers to Mayfair in London, in order to conjure up the appropriate social status for the hero’s house.

“But the house of Glaucus was at once one of the smallest, and yet one of the most adorned and finished of all the private mansions of Pompeii: it would be a model at this day for the house of ‘a single man in Mayfair’.… ” (LD: 37) Using English values to denigrate Roman society, is a fairly typical feature of the book. In “A Fashionable Party and a Dinner à la Mode in Pompeii”, the narrator makes a direct comparison between the (supposed) Roman custom of openly admiring a host’s artworks and the more restrained aristocratic English custom of politely ignoring them, “….. they spent several minutes in surveying the apartment, and admiring the bronzes, the pictures, or the furniture, with which it was adorned – a mode very impolite according to our refined English notions, which place good breeding in indifference. We would not for the world express much admiration of another man’s house, for fear it should be thought we had never seen anything so fine before!” (LD: 257)

1

1 2

2 3

3

|