1

1to the Greeks do hold this opinion of the Romans, and since this opinion is spreading more and more among foreign nations, I deem it to be fitting for one of my profession to examine the whole matter more thoroughly, so that, when all the arguments have been weighed, it will become easier for the fair-minded to decide what judgement he should make”. (Magnificenza ed Architettura de Romani, 1761-62; in Lorenz Eitner, Neoclassicism and Romanticism 1750-1850, Volume 1.)

In the end, Piranesi’s attempts to reinstate the dignity and significance of Roman art was a glorious failure. Not only because the ever growing number of Fine Art Academies were predicated upon Winckelmann’s theories concerning the supremacy of Greek art, but because his own zeal seduced him into producing reconstructions of Roman antiquity that were so fantasized that they often looked absurdly confusing.

Roman Wall-Painting and Cinematic ‘Reconstructions’

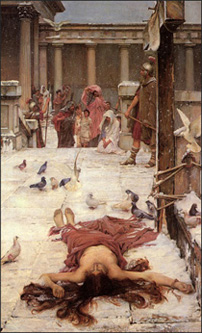

Film, Television and Computer Games are some of the recent filters to stand between the contemporary viewer and ancient Roman wall-painting (fig.1). Their ubiquitous presence along with their dynamic capacity to blend fact, faction and fiction makes them the primary mechanisms for shaping popular perceptions of antiquity. In addition to their hegemony, they have also subsumed many of the earlier influential filters that originated with the visual and performing arts. Lytton’s novel The Last Days of Pompeii is a case in point, because it provided the narrative for the first feature-length movies responsible for establishing the 'disaster' genre (fig.2). In addition to this genre, Roman history in general played a significant part in the evolution of cinema, from silent films through to epic blockbusters. Ridley Scott's Gladiator and its clones are recent examples. One of the primary reasons for our fascination with ancient Rome stems from the real and imagined conflict between Roman Republicanism and Imperialism. Real in the sense that much of its literary and visual culture survived more or less intact, and imagined in the sense that what survived became a surrogate for Classical antiquity and a catalyst for its Renaissance and Neoclassical revivals. They in their turn became an indistinguishable part of the footprint of Roman history. By the early twentieth century popular culture had merged both the real and the imagined and cinema reinforced this by drawing upon them equally to create its own historical visualisations. And where better to look for those early pictorialisations than nineteenth-century romantic paintings by artists such as Jacques-Louis David, Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, William Waterhouse and Alma-Tedema (figs.3&4).

1

1 2

2 3

3

|