1

1In Germany Neoclassical architecture was promoted via the work of Karl Friedrich Schinkel (1781-1841), who visited Pompeii in 1824 some 40 years after Soane. Schinkel later become one of Germany’s most important Neoclassical architects and significantly contributed to Berlin’s Neoclassical appearance (Fig.1). In a letter to his architectural tutor David Gilly (1748-1808), Schinkel revealingly wrote, "When it comes to antiquity, it offers nothing new to an architect because one is from childhood familiar with it." Clearly he was not referring to actual antiquity, since he did not become ‘familiar’ with it until he was 42 years old. Like so many other influential figures he first experienced it through the filter of an earlier form of classical appropriation, such as the Baroque Style.

The British architect Charles Cameron (1740-1812) also played an influential role in internationalising the Neoclassical style via his work for Empress Catherine the Great of Russia (fig.2). As a result of his 1772 publication The Baths of the Romans explained and illustrated, with Restorations of Palladio corrected and improved, Catherine commissioned him to produce architectural and interior designs for her country palace at Tsarskoye Selo and Pavlovsk situated outside of St Petersburg. Many of the interior features were based upon wall-paintings from Rome and Pompeii. The Grecian Hall at Pavlovsk and the Grand Hall in Catherine’s private apartments at Tsarskoye, bare strong resemblances to Adam's Marble Hall at Kedlestone Hall (1760), produced some twenty years earlier (fig. 3).

Dilettantes and Pattern Books

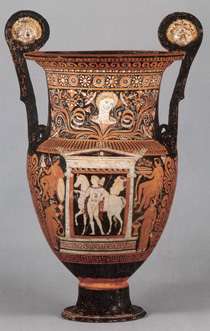

Dilettante collectors such as Sir William Hamilton (1730-1815), the English Ambassador to the Court of Naples between the years 1764-1800, acquired impressive amounts of antiquities. His 750 Etruscan vases; 300 glass pieces; 125 terracottas; 627 bronzes; 150 ivories; 150 gems; 6000 coins, later become the foundation of the British Museum’s Greek and Roman collection (Fig.4). Hamilton and the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, were amongst the first to express concern at the removal of prized sections of wall-paintings, which caused the material evidence to be fragmented. (see Jenkins and K. Sloan, 1996, Vases and Volcanoes: Sir William Hamilton and his Collection, London, The British Museum Press.)

1

1 4

4 3

3 2

2

|