2

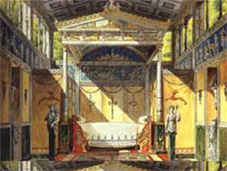

2The material evidence from Pompeii and Herculaneum was further fragmented and decontextualised by the increasing number of Pattern Books produced in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth century. Most of them were derived from ‘decorative’ motifs found in wall-paintings, stucco-work and architectural details. Some of the designs, such as those produced by Charles Percier (1764-1838) and Pierre Fontaine (1762-1835) were taken directly from wall-paintings (fig.1). Others merely referred to other illustrated publications such as the eight volume Le Antichità di Ercolano esposte, published between 1759-1792 by the Royal Herculaneum Academy (fig.2), or D’Hancarville’s 1766 publication Collection of Etruscan, Greek and Roman Antiquities from the Cabinet of the Honourable Wm. Hamilton (fig.3) and Abbé de Saint-Non’s 1781 Voyage pittoresque ou description des royaumes de Naples et de Sicile with illustrations made by a Dominique-Vivant Denon and others.

Percier and Fontaine became Napoleon's favourite architects and interior designers and consequently their pattern book Recueil de Décorations Intérieures (1812) had an enormous impact upon French taste and significantly contributed to the creation of the French Empire Style, which incorporated Pompeian motifs into politicised designs emblematic of Napoleon’s political ambitions (fig.4).

The Pompeian Style

The introduction of the Empire and Pompeian Style, along with the various architectural recreations associated with them, such as Ludwig I of Bavaria’s House of Castor and Pollux, Queen Victoria’s Pompeian Garden House (1884) and Prince Napoleon’s Palais pompéien (1857), laid the foundations for our depaganised view of Roman wall-painting (figs.5-7). Like Raphael’s stylised appropriations two centuries before, they appeared to have the gravity and exoticism of an historical artefact, whilst in reality being decontextualised pastiches. The knock-on effect of this was that the pagan originals were stripped of their symbolic value and instead became decoration, in the modern sense of the word. Neoclassicism’s cultural, political and scientific agenda, underpinned by the Industrial Revolution, embedded the iconography of Pompeii and Herculaneum into world culture and in so doing, created one of the most opaque filters through which we now view the art that emerged from these cities.

2

2 5

5 4

4 1

1

|