1

1The cultural constructions that the nineteenth-century Grand Tourists went in search of were infinitely more subtle, and therefore probably more deeply experienced, than those marketed by today’s tourist industry. Instead of blue skies, white sandy beaches and a quick cultural fix, their accounts indicate that they desired exposure to highly poetic visions in which reality, poetry and myth merged. Hence, it was necessary to relive the dream and experience the Colosseum, Pantheon or Pompeii's Forum at sunrise, sunset or in moonlight, because artists and writers had pictured them in this context (fig.1).

Fragments, Fakes and Grotesques

In addition to the romanticisation of Italy’s cultural history, less scrupulous parts of the tourist industry were busy ‘reconstructing’ if not faking antiquity. It was not uncommon for restorers such as Bartolomeo Cavaceppi to piece together unrelated sculptural fragments and then sell the ‘restored’ piece to an unsuspecting collector or tourist. Although supposedly site-specific, the wall-paintings fared no better, because the powerful elite were allowed to acquire them (fig.2). The Spanish, Bourbon and Napoleonic dynasties that ruled Naples used them to decorate palaces and gave others to visiting potentates. The majority of tourists and connoisseurs contented themselves with cheap copies, mostly in the form of hand-coloured prints that oversimplified the original paintings and made them appear mechanised (fig.3).

The removal of wall-paintings and massed produced copies skewed the dynamic relationship between them and their location, content and pictorial space. Removal turned paintings into dislocated fragments and copies turned inter-textual motifs into individual pictures. The wall-paintings that were once part of the villa of Publius Fannius Synistor at Boscoreale are a prime example of this. In the early twentieth century they were removed and auctioned in Paris and now reside in museums as far apart as Naples, Brussels, Amsterdam and New York. As a result of this supposedly pragmatic destruction, the paintings are undoubtedly much better preserved, although their original context has been completely destroyed. One of the most important Second Style paintings in Pompeii, situated in the oecus corinthius in the House of the Labyrinth, was recently damaged because the concrete roof that was supposed to preserve it collapsed on top of it. Numerous other paintings have simply faded away due to the enormous problems associated with the preservation of an entire city. In 1965 the emphasis switched from excavation to conservation, which left approximately 55 of the 165 acres site still buried. The enormity of the conservation problem is so great that Pompeii will always remain on the World Monuments list of Most Endangered Sites.

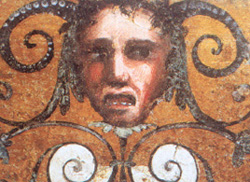

As copies and copies of copies, as well as inventions in the ancient style proliferated throughout Europe, the ‘original’ ancient paintings became increasingly trapped in a mise-en-abyme of their own inadvertent making. Due to a quirk of fate Raphael’s wall-paintings in the Style of the Ancients and the numerous copies that followed, such as those still preserved in the Loggia Mattei on the Palatine Hill in Rome, became known as grotesques or grotteschi (figs.4-5). The etymology of this word is symptomatic of the way in which the invented versions were viewed. Initially grotesque simply referred to motifs derived from paintings found in grottoes, which were later revealed to be the subterranean earth-filled vaulted ceilings of the Domus Aurea, Nero’s Golden Palace (fig.6).

1

1 2

2 4

4 5

5 6

6

|