1

1Over the years, however, grotesque came to signify anything that was horrifyingly ugly. This crude reading distanced contemporary viewers from the possibility that earlier generations attached symbolic meaning to the synthesis of man, animal and vegetation. Numerous eighteenth-century paintings, sculptures and publications featuring grotesque imagery, paved the way for modern horror film adaptations that make the ancient grotteschi seem relatively restrained (figs.1&2).

Pompeii as Surrogate for the Lost Greek World

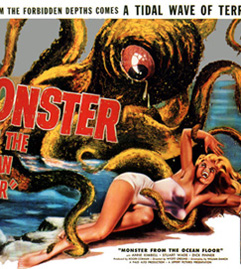

Publications such as Thoughts on the Imitation of Greek Works in Painting and Sculpture (1755) and The History of Ancient Art Among the Greeks (1764), by the German art historian Johann Joachim Winckelmann, challenged existing perceptions of Roman art and promoted a ‘Greek revival’ that demoted Roman art to the status of imitation. As a consequence, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth century, Roman wall-paintings were increasingly regarded as a copies of lost ‘superior’ Hellenistic originals. Even fairly recent publications continued to label them as such, without providing any substantiating text. Winckelmann did not attempt to prove the supremacy of Greek art via painting, but by arguing that because the majority of ancient Roman sculptures were copies of lost Greek originals the creative superiority must therefore lie with the Greeks. Prior to Winckelmann, Italians such as Scipione Maffei and Matteo Lucchesi, conducted similar debates using examples of Greek, Etruscan and Roman architecture to prove or disprove the primacy of one culture over the other. Unfortunately, when notions of primacy and supremacy enter the cultural arena then culture itself suffers. Hence, perceptions of Greek and Roman art became increasingly inflated and the legacy of the ensuing confrontations remains with us to this day. For example, the architect and engraver Giovanni Battista Piranesi, attempted to counter Winckelmann’s thesis by producing etchings and writings that eulogised Roman art in terms that were as equally inflated as those used by Winckelmann to describe Greek art (fig.3). The artist Henry Fuseli (1741-1825) went even further and openly blamed Winckelmann for misleading generations of German artists whose work, in his view, had become sterile and expressionless, largely as a result of adopting Winckelmann’s austere interpretation of Greek classicism. (see John Knowles, 1831, The Life and Writings of Henry Fuseli. London, II: 13-15. Fuseli translated Winckelmann’s Reflections on the Painting and Sculpture of the Greeks, into English in 1765.)

Piranesi’s highly fantasised engravings of ancient Rome were contemporary with the early discoveries at Pompeii and Herculaneum. As such they provide us with valuable insight into certain aspects of the Italian psyche and its relationship to its past. His work, and that of others like him, located the emerging wall-paintings in a cultural framework that enlightened and at the same time distorted contemporary readings. With the benefit of hindsight, it is now apparent that both he and Winckelmann were equally guilty of inventing as well as revealing the past, but for quite different reasons. Piranesi’s grandiose recreations of Roman culture were clearly augmented realities motivated by national pride in the physical remains of Roman Imperialism. Although he produced very little in the way of architecture, his impact on European visual culture and its perception of Roman antiquity was enormous. This was largely achieved via profusely illustrated publications such as his four volume Le Antichità Romane, 1756 (The Antiquities of Rome) and Della Magnificenza ed Architettura de’Romani, 1761 (On the Grandeur and the Architecture of the Romans).

1

1 2

2 3

3

|