Breton’s claim that Picasso and de Chirico significantly changed “visual forms of representation” is amply born out by their influence on six major twentieth-century art movements: Cubism; Pittura Metafisica; Neue Sachlichkeit; Surrealism, Abstract Expressionism and Transavantguardia. Both were extremely prolific over nearly eight decades and like da Vinci and Michelangelo their compulsion to continually create may well have been driven by pathological desires linked to cathartic sublimation. In both cases their desire to be prolific was not only underpinned by novelty but also by purposeful repetitiveness. Creative repetition is a condition that often manifests itself when trauma, caused by childhood loss, is a formative element in an artist’s work. The significance of this observation will become apparent later in this essay when discussing de Chirico’s

Il grande metafisico (1917) and the numerous

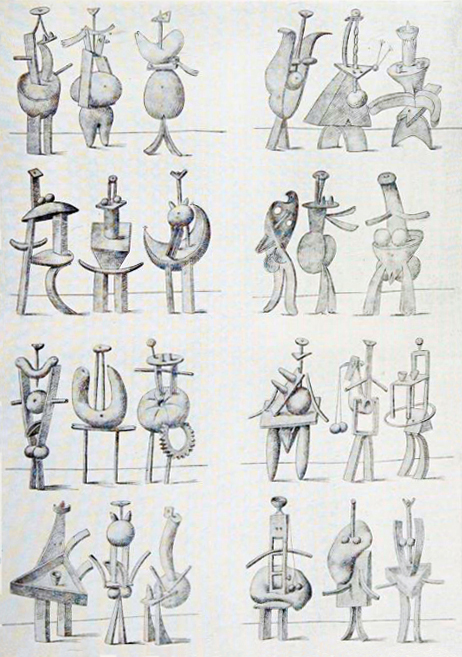

Piazza d’Italia paintings (1913-1971) (Fig. 1) and Picasso’s 1933

Une Anatomie drawings (Fig.2).

Prolific creativity can of course be attributed to any number of benign and not so benign motivations such as the will to possess, machismo, sexual drives, insecurity complexes and an attempt to cheat one's inevitable demise. In the case of both Picasso and De Chirico, however, the evidence lies before us in the taxonomy of their oeuvre and in an analysis of the themes that they repeatedly used. In the case of both artists a chronological ordering of their work is of comparatively little conceptual value, in contrast to the revelations that emerge from an analysis of their thematic groupings and the repetitive visual patterns that occur within them. Even a brief study of their respective taxonomies indicates that both artists revolved around opposing gender loci.

2

2 1

1