4

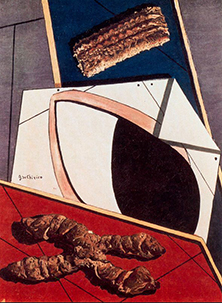

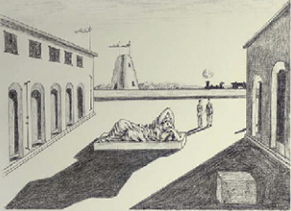

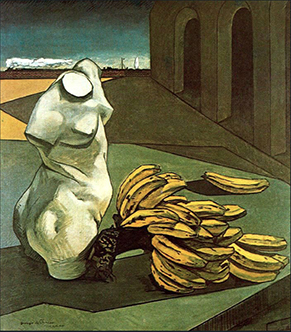

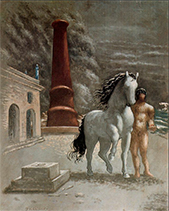

4In terms of pictorial expression the themes were communicated via depictions of: Italian piazzas, mannikins, Greek Gods and Goddesses, votive food, self-portraits, archaic and Risorgimento statues, horses, centaurs, gladiators (in domestic interiors), Roman charioteers and Knight Errants (Figs.1-10).

6

6 2

2 7

7 5

5 1

1 3

3 9

9 10

10 8

8