4

2

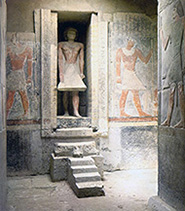

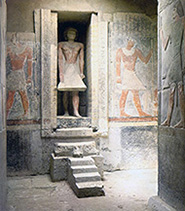

1.Egyptian false-door with steps leading to an offering table. Mastaba of Ti, Sakkara Egypt (Fifth dynasty c.2494 – 2345 BC)

2. False-door Tomb of the Augurs, Tarquinia, Italy, c. 550 BC

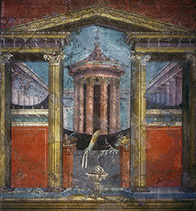

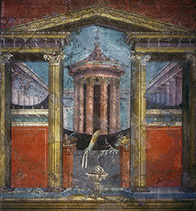

3. Villa di P. Fannius Synistor, tholos, Bedroom M, lateral west wall

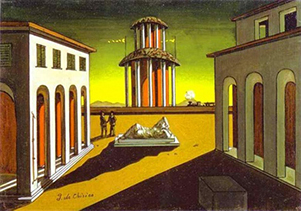

4. Giorgio de Chirico Piazza d'Italia 1913

Each theme is intensively pursued and exhaustively reworked, but nevertheless there is a sensibility that connects them. One has only to scan through his Catalogue Raisonné to become aware of the all-pervading melancholy that permeates every theme. But it is not the dour Germanic kind, because it is tinged with Italianate hope and renewal and set in a place where Ariadne, Dionysus and Apollo meet. De Chirico came to terms with loss of childhood, adolescence and personal bereavement by creating toy-like meta-worlds in which mytho-heroic male phantoms inhabit an equally male dominated landscape made up of phallic canons, artichokes, condottieri, steam trains and statues that memorialise Risorgimento frock coated gentlemen. In this meta-world or metaphysical landscape as Guillaume Apollinaire described it, the classical past is retrieved and transmuted into a benign Pythagorean world tinged with autumnal irony and an underlying sense of spatiotemporal discontinuity.

Piazza d'Italia 1913 - 1969

“What is it our pleasure to paint today?” …was a phrase that De Chirico, according to his memoirs, recited every morning when sitting down in front of his easel. In some instances he painted the same theme over and over again, such as in the Piazza d’Italia series of paintings. They are without doubt his most restated compositions and numerous examples were produced during his lifetime (Fig.4).

Some critics have attributed this repetitive act to purely mercenary gain, mental laziness or lack of inspiration. However, even a cursory reading of these works reveals the significance behind their formulaic compositions. Put simply, their iconography reveals them to be a type of ex-voto painting and as such places them outside of any modernist canons of reductive uniqueness. On the contrary they reaffirm ancient visual practices involving metaphysical perspective and its relationship to dissolution and becoming. The numerous Piazza d’Italia paintings represent the false-door between De Chirico and his own patriarchal lineage. The very fact that these paintings were produced in large numbers, with slight variations, enabled De Chirico to engage in a repetitive act of apotheosis, which was at the same time, a pictorial reaffirmation of his sense of geographic fatality. This was the phrase that he used to denote his belief in the inevitability of geo-genetic spiritual interconnectedness, which in his case he felt existed between him and his Greco-Roman ancestry.

The Piazza d’Italia series, referred to earlier, in all its numerous manifestation is very much the key to the paternal principle that motivates many of De Chirico’s themes. The significance of its iconic narrative and its enigmatic pre-surrealist dream like qualities can only be fully understood by referring to another much more ancient prototype — the Second tragic-style of Pompeian painting (80BC), which is itself probably a development of earlier Etruscan and yet earlier Egyptian tomb iconography (Figs.1-3). To all intents and purposes they all represent, including De Chirico’s modern manifestation, an act of atavistic apotheosis, especially in the case of the latter since his paintings exemplify numerous pictorial interfaces between son and deceased father. Compositionally speaking he uses the enigmatic link between metaphysics and perspective to achieve this ancestral reunion, as did the artists in 80BC who created the tragic-style. He even re-invokes much of their imagery such as the tholos, as the symbol of memorialisation, dissolution and becoming, the ‘wall’ as a symbolic barrier between physical and metaphysical worlds, the peristyle to indicate deep space and the placing of ex-votos to attract and assuage the divinities alluded to in his paintings. In the opening pages of his memoirs he affectionately and proudly described his father

4

> 3

3 1

1

as having all the noble and dignified qualities of a nineteenth century gentleman and clearly admired him for being an aristocrat libertarian who chose to contribute to society by working as an architect-engineer. His son also admired him for having fought duals with pistols. Despite the obvious father son affection that existed between them we are made aware of the reserved manner in which it manifested itself, mainly through a lack of emotional or physical contact or gesture, except that is until a few days before his father’s death.

Whilst they were out walking, his father unexpectedly stopped and embraced him and at the same time announced to him that his life was coming to an end. At the same time he comforted his son with the thought that his life, in contrast, was just beginning. As they walked home his arm remained around his son’s shoulder. A few days latter his father who had been suffering from a terminal illness took to his bed and died. A projection of this last embrace occurs in numerous paintings by De Chirico, but with a poignant difference.

2

2 3

3 1

1