1. Giorgio de Chirico

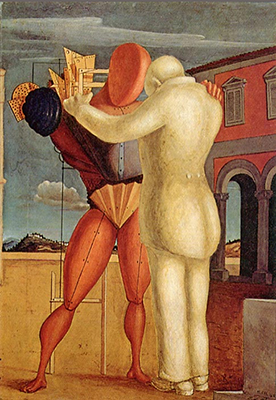

The Return of the Prodigal Son 1922

2. Giorgio de Chirico The Grand Metaphysician 1917

3. Maurice Owen The Grand Metaphysician according to a 60°/30° and 45°/90° set square,

bronze, after Giorgio de Chirico The Grand Metaphysician 1917

The tragic embrace that preempted his father’s death is transposed into an embrace denoting greeting and reconciliation and the series of paintings that best exemplifies this is

The Return of the Prodigal Son (Fig.1). In this series the father figure is depicted as a typical nineteenth century frock coated statue that appears to have descended from its plinth in order to embrace the redeemed prodigal son. Clearly there are many ways of reading this image, other than on a pathographic level. It could well relate to the artist’s own sense of returning to the craft, to tradition and to a reaffirmation of the skills of previous generations of artists. In his essay “The Return to the Craft” in

Valori Plastici, 1920, De Chirico, amongst other things extols the virtue of drawing from statuary, i.e. embracing statuary as a pedagogic exemplar. Whilst this may open up avenues of interpretation, it does not run counter to the fact that it is the image of his father’s generation that is used to symbolise the return to that which is lost. The personal reunion is given further emphases by the assembled draftsman’s drawing tools that are used to construct the figure of the redeemed son and which were very much the tools of his father’s profession. The reunion is made doubly ironic by the fact that in De Chirico’s temporally discontinuous world, one cannot escape the enigmatic sensation that perhaps it is not only the son who is returning, but by implication also the deceased father, who has stepped down from his plinth.

One of the paintings that best exemplifies De Chirico’s patriarchal bias is the 1917 version of

The Grand Metaphysician (

Il grande metafisico ) (Fig.2). Between 1973 and 1980 I carried out an in-depth study of this painting which involved creating three 3-dimensional versions of the central statuesque assemblage —

The Grand Metaphysician. The study revealed many of the key principles underlying De Chirico’s use of metaphysical perspective and its links to ancient Roman wall-painting, and the way in which both used similar forms of linear and atmospheric perspective to create metaphysical worlds dedicated to ancestral worship.*

In terms of his patriarchal (ancestral) bias the study highlighted the fact that the central statuesque figure was a metonymic portrayal of his deceased father symbolically clad in the accoutrements of his profession (Figs.2&3). The near subliminal presence of Odysseus located at the far end of the central piazza gives the painting a katabasis-like atmosphere, which not only implied Odysseus's return to his family, but also that of the piazza's central paternal motif. For more on

Katabasis see my essay:

“Giorgio de Chirico e il Tempio dell’Immortalità”

* For more on the 3-dimensional aspect of the study see :

The Spirits Released :

De Chirico and Metaphysical Perspective.

1

1 3

3