8

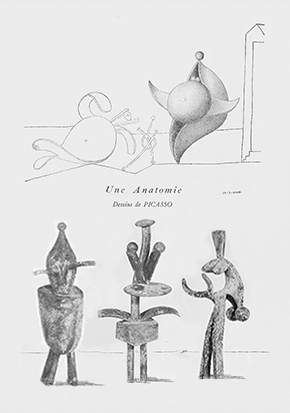

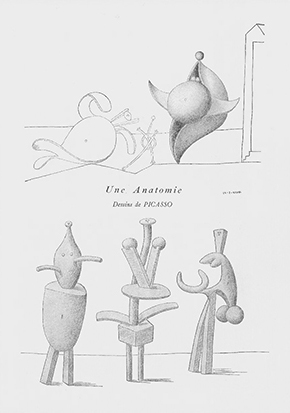

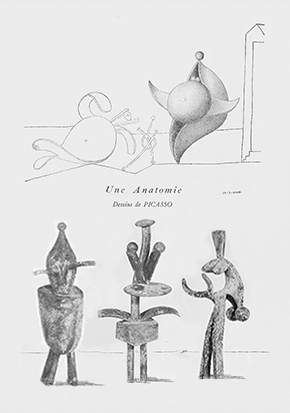

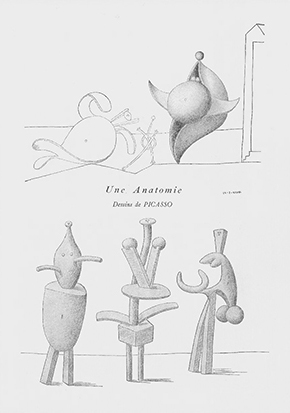

1. Pablo Picasso Une AnatomieTwo women and Ithyphalic Male, drawing, 25-03-1933.

2.

Minotaure, Issue 1, 1933, Une Anatomie : Dessins de PICASSO, title page.

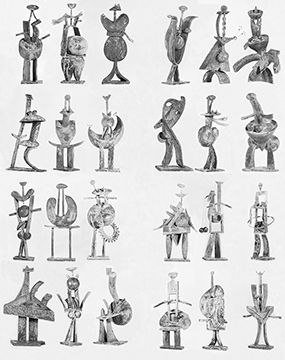

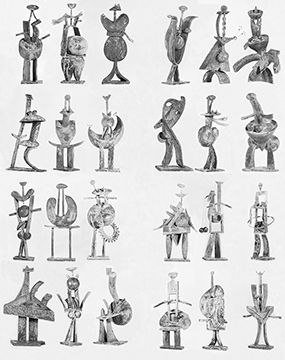

3. Minotaure, Issue 1, 1933, Une Anatomie : Dessins de PICASSO, title page, bronze transcriptions by

Maurice Owen, 1999.

4. Pablo Picasso, 1933, Une Anatomie : Dessins de PICASSO45. Pablo Picasso, 1933,

5.

Une Anatomie : Dessins de PICASSO, bronze transcriptions by Maurice Owen, 1999.

The Gender Significance of the Une Anatomie drawings 1933

The

Une Anatomie drawings feature 26 skeletal female figures and one male. The male is depicted as a penis on legs. Its ithyphallic presence might lead the viewer to conclude that the drawings signify a Dionysian gathering of women around a single omnipotent male, but this could not be further from the truth (Figs.1).

After a lengthy study of these drawings, which included 3-dimensional transcriptions (Figs.2&5), it seems more likely that Picasso intended them to have an ex-voto healing function relating to his then mistress Marie Thérèse-Walter. At the time the drawings were produced she was suffering from a life-threatening illness that caused serious weight loss and her normally athletic body had become "skeletal”.

For more on this see my essay: Une Anatomie 1933-2022

3

3  2

2

4

5

1

18

3

3  2

2 4

4 5

5 1

1