9

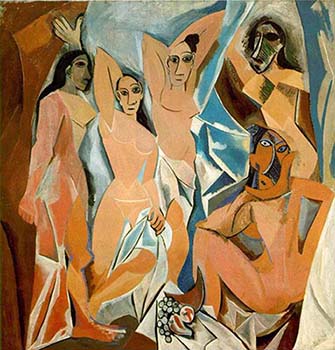

1. Pablo Picasso Les Demoiselles d'Avignon 1907

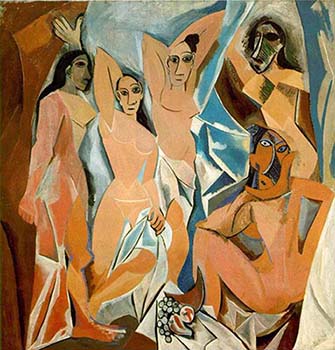

2. Pablo Picasso Trois femmes à la source d'eau, 1921

Collectively, Picasso’s oeuvre constitutes a visual autobiography that functions as a commentary and eidetic signifier, (eidetic in the sense of acting as a catalyst for our collective and personal memories). Each painting, drawing, print or sculpture is both a fragment, a unique statement and part of a collective vision. Of the many themes that run through his work, his relationship with women was undoubtedly the most important. To a large extent this was shaped in infancy. As the male heir, Picasso grew up according to middle class Spanish custom surrounded by women and by all accounts they pampered him. His dependence on women is well documented, as is his own ambiguous “Goddess to doormat” treatment of the women that shared his life. His choice of Picasso as his signature clearly indicates his preference for the matriarchal line, since he chose it in favour of Ruiz, the more distinguished family name on his father’s side. In terms of his sexuality, he clearly acknowledged the importance of women in his life, although at the same time fearing his dependence upon them. He claimed that both his sexual desires and creative instincts arose simultaneously and thus in his work creativity was iconographically synonymous with procreativity. According to Picasso, both transitions occurred during his pre-adolescent childhood, thus causing him to move into manhood without having experienced the adolescent phase (a confession that is ripe for psychoanalytical analysis). However, Spanish machismo rather than truth may well lie behind such a claim since implicit in it is the notion of the child genius.

In reality, his sexual initiation probably took place in a brothel in the Barrio Chino, Barcelona’s red light district at the turn of the century, whilst he was in his mid-to-late teens and an art student at the Art Academy of that city. The brothel latter surfaced in what has become one of the seminal images of modern art. Now politely referred to as Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907), the afro-Egyptian-cubist women (and possibly single male figure) depicted in this seminal work appear to be gathered around an arrangement of fruit (Fig.1). The fruit’s phallic symbolism is quite explicit and fairly typical of the metonymic-symbolic visual coding by which artists indicate a sexualised male or female presence. Picasso’s love of keys, in actuality and pictorially, is well documented and at times they too would become sexualised indicators of the subliminal male presence, as in his beach cabin series, which featured young women playing ball on a beach and using large keys to open the cabins. If we exclude the classicised male figures in Picasso’s Minotaur series, we are left with mainly symbolic references to the male presence, in an otherwise mainly female world. This was something Françoise Gilot, his partner for nearly ten years, noted in her book Life with Picasso.

Just prior to painting the seminal Les Demoiselles d’Avignon Picasso made the then arduous journey to a small Pyrenean village called Gósol, were he spent more than two months working and searching for new inspirational directions free from the intellectual constraints of Madrid, Barcelona and Paris. During that time he produced work that came to be known as his Rose Period. Picasso en Gósol 1906 * and Picasso 1906 : the turning point **, both document his significant shift towards an art dominated by the female form, an aspect of which is displayed in his fecund matriarchal images that bare witness to De Chirico's observation concerning "big women" (Fig.2).

* Picasso en Gósol, 1906, by Jèssica Jaques Pi. 2007

** Museo National Centro de Reina Sofia, Madrid, nov. 23 - march 24.

1

1 2

29

1

1 2

2