1

1scenery. He clearly attributes the proof of this linkage to Vitruvius when he says, "The assumption that the vista elements of the style are scenographic is based upon two passages in Vitruvius. In the one he specifies the inclusion of painted scaenae frontes in the structural style when tracing its evolution; in the other he describes the setting of the contemporary stage." His accompanying note 3 then listed the following writers who built on the "assumption" that "VII, v, 2 and V, vi, 8." provide the written evidence for linking stage scenery to the "structural style" in Romano-Campanian wall-painting: "E. R. Fiechter, Die baugeschicht. Entwickelung d. ant. Theaters, Munich, 1914, pp. 42 ff. and 102 ff.; A. Frickenhaus, Die altgriechische Bühne, Strasbourg, 1917, p. 48, pl. I; M. I. Rostovtzeff, J. H. S., XXXIX (1919), p. 150 ; E. Pfuhl, Malerei und Zeichnung der Griechen, Munich, 1923, II, pp. 810, 812, 868, 872, 897; H. Bulle, Abhand. d. Bayer. Ak. Ph.-Hist. KI., XXXIII (1928), pp. 306-332." (Little 1936 : 407) This list has grown exponentially, since the publication of Scaenographia, to include just about every subsequent writer concerned with Graeco-Roman theatre.

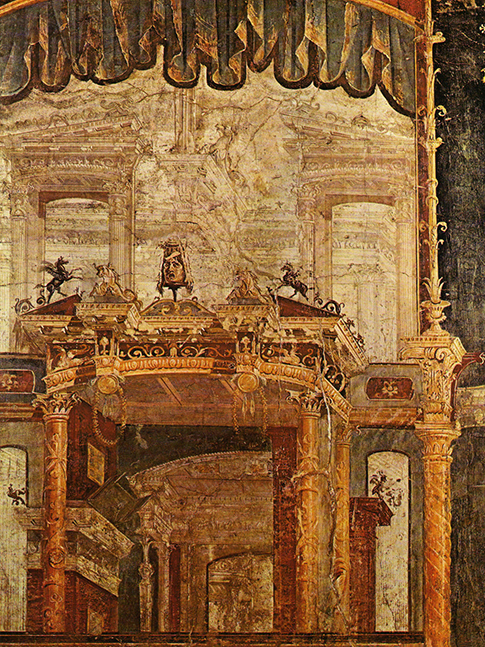

Whilst I tend to agree that some form of overlap occurred between stage scenery and domestic wall-painting, I would argue that this link cannot be made on the basis of Vitruvius's use of the words scaenae frons or scaenarum frontes. Nor can it be made on the basis of visual evidence that 'appears' to resemble theatre scenery, but for which there is no further corroborating evidence. A Palaestra panel from Herculaneum is a classic example of the type of misrepresentation that can occur when evidence is solely based on visual similarities (fig.1). This panel appears to represent the typical proscenium-arched theatre, complete with draped curtains. Even the red colour of the proscenium arch evokes the ubiquitous nineteenth-century Italian theatre. Its uncanny likeness begs the question, how is it possible that this pictorial fragment, produced two thousand years ago, can represent a type of theatre that only came into existence in the nineteenth century?

The answer to the above question is relatively simple and it lies in the decor for the earliest Italian proscenium theatre - Teatro di San Carlo in Naples, which opened in 1737. Following its destruction by fire in 1816 it was redesigned by Antonio Niccolini who, in addition to being an architect and scenographer, was also the director of the Accademia di Belle Arti, Naples. Whilst designing the theatre's interior and the enlarged proscenium, he was also engaged in editing a 24 volume treaties on the artefacts and wall-paintings found at Pompeii and Herculaneum. Hence, it is very likely that paintings such as the Palaestra panel, may have influenced his designs for this theatre. Fausto and Felice Niccolini continued their father's work and in 1854 published Le case ed i monumenti di Pompei disegnati e descritti (Drawings and descriptions of the houses and monuments of Pompeii). In this publication they attempted to illustrate all the excavated public and private houses and monuments in Pompeii, along with numerous examples of artefacts and wall-paintings. Fausto also worked with his father on the 1844 redecoration of the Teatro San Carlo, which resulted in its current red and gold appearance. If wall-paintings such as the one found in the Palaestra at Herculaneum helped to shape the early proscenium style theatres, that does not make them depictions of theatres. For more on this see Fantasy Architecture.

1

|