1

1True to the satirical nature of the Satyricon, Trimalchio requests the opposite metaphor on his tomb, “I want you to carve ships under full sail on my monument, ..” (Petronius Satyricon Chapter 71). Statius, whose poetry focuses upon the area around the bay of Naples, provides us with a rich understanding of the way in which poetic and painted views such as these resonated with sacred and metaphorical associations, often relating to tranquillity and safe passage. (see Statius Silvae. Loeb Classical Library, Mass., 1982and Bonner 1944).

Plate 16, whilst not elaborated upon other than in the lengthy caption, is nevertheless used to add weight to the book’s thesis. However, not only can the content of such paintings be interpreted in ways that counter this thesis, but its probable date of production also mitigates against the book’s premise, which is that the nouveau riche profited from the earthquake of 62 A.D and in so doing used their new found wealth to ‘imitate’ the luxuriousness of the Hellenistic world. Bettina Bergmann made a study of some three hundred such paintings and came to the conclusion that the majority of them were produced ‘in the early Fourth Style between 50 and 62 AD'. If correct, this places them before the earthquake, which supposedly allowed the middle class to prosper.

Zanker was not alone in his selective use of wall-paintings found in the tablinum of the house of M. Lucretius Fronto. Other historians also used elements from its richly painted interior to support different theories. The most notable was H. G. Beyen who selectively used imagery from the top sections of the tablinum’s lateral walls to recreate ancient stage sets. He did this without making any significant reference to the rest of the paintings in the room. The recreations were then used to support arguments that Roman-Campanian wall-painting was derived from ancient stage scenery. The tautological issues surrounding Beyen’s reconstruction methods will be fully explored in the forthcoming chapter House as Theatre.

Game parks or paradise gardens?

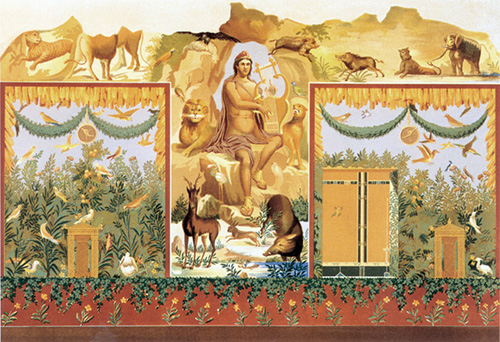

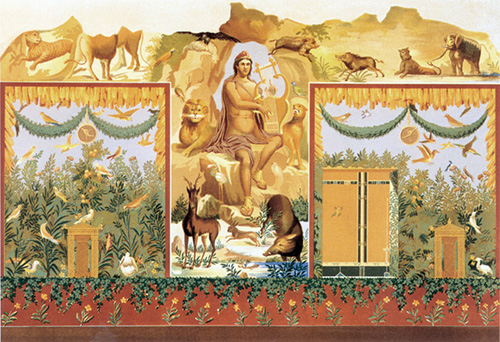

According to Zanker it would appear that nothing was beyond the desire of middle-class Pompeians if they could find a way of ‘imitating’ the object of their desire - not even royal game-parks. This proposition is illustrated by referring to a wall-painting located in the garden of the House of Orpheus (Plate 14.2) (fig.1). The physical and financial unattainability in this instance is not symbolised by the royal villa but by the even more exotic image of the private game park, which only royalty or the fabulously wealthy could afford. His illustration is a lithographic copy of this now degraded wall-painting and the caption informs us that we are looking at a ‘game park’ in which Orpheus can be seen using his lyre to enchant wild animals. Despite the fact that Orpheus is the subject of the painting he gets second billing to the image of the ‘game park’. Why has the author taken Orpheus out of the wilderness and placed him in a royal theme park? Does the image of the cave that he is seated in front of mean nothing in mythological terms or was it just another one of the theme park attractions?

1

11 Lithograph (1875) depicting a garden wall-painting in the House of Orpheus (VI 14.20), Pompeii, it corresponds to Plate 14.2, Pompeii - Public and Private Life, 2000.

|