1>

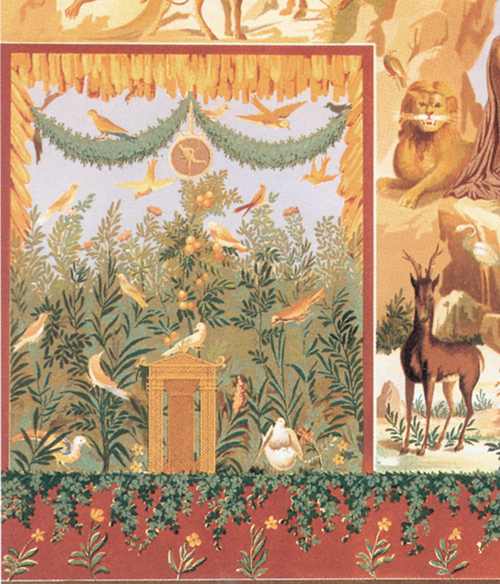

1>After having conjured up the image of the game park in relation to this painting we are then told that the two ‘inserts’ that constitute somewhere between a third and a half of the painting, are depictions of villa gardens, thus completing the circle between game park and villa. But Zanker seems to have overlooked an important visual element that runs along the top and sides of the inserts. A jagged rocky edge has been used to frame them, which implies that we are looking into or out of yet more caves (fig.1). Although the directional aspect is ambiguous the garlands and the outward facing images on the terracotta coloured circular tablets seem to infer that we are looking into a highly stylised cave entrance. This makes more sense if we refer back to the cave entrance depicted behind Orpheus and link it to the image of the chthonic paradise that is an essential part of Orphic myth.

In the context of Orphic myth the juxtaposition of the Orpheus section and the two inserts becomes perfectly logical. In the upper zone we are shown conflict in the form of predatory animals chasing cattle, a bird appears startled and is protecting its nest. As we move down the scene becomes tranquil as Orpheus’s music begins to enchant the wild animals, which no longer threaten one another. The stylised cave entrances, possibly symbolising the Orphic decent into the underworld to rescue Eurydice, help frame the theme of a fertile and blissful world peacefully echoing to the sound of bird song. Man’s presence in this garden paradise is symbolised by the rustic shrine-like structures, the garlands and the terracotta tablets possibly signifying a divine presence. In this context the ‘inserts’ signify a glimpse into Orphic paradise and not covetous views into villa gardens, as the book would have us believe.

So far we have concentrated on the illustration and its caption. The thesis exemplified by this image, but never referenced, appears several pages later in a subsection titled "Large Pictures for Small Dreams" (p. 184-192). As the title suggests it revolves around the idea that large pictures, in this case wall-paintings, were used in relatively small houses to satisfy their owner’s unattainable desire for opulent villas and the luxurious lifestyle that presumably went with them. Given this thesis, this section might have been more appropriately titled ‘Small Pictures for Large Dreams'. However, it would seem that despite the fact that they could pay for large expensive paintings, ultimately these only represented the ‘small dreams’ of men whose wealth was insufficient to realise their ‘hedonistic’ ambitions, which was presumably to own actual game parks. Having established this as the reader’s frame of reference, page 187 goes on to describe the Orpheus painting as a mythologically enriched paradeisos, having earlier described it as a game park. However, any illusions that the reader might have concerning its mythological status are quickly dispelled by referring them to a passage in Varro’s Res Rusticae (3.13.2-3). The passage describes an open-air dinner in the game-preserve of Quintus Hortensius to which a person impersonating Orpheus is summoned. When asked to sing he instead blows a horn that attracts the various animals in the reserve. Despite the existence of numerous other images and texts that act out the Orphic legend, we are asked instead to substitute them all for this horn blowing Orpheus in a game park; thereby linking the painting with the unattainable lifestyle of the fabulously rich. And yet, somewhat surprisingly, we are also told that it was ‘immaterial’ as to whether or not the owner of the painting understood this link (p.187).

1 Detail from the Orpheus lithograph (previous page) showing the inserted section on the left side, in which the jagged edge of a stylised cave is clearly visible.

|