1

1But surely if he was not aware of the significance that Zanker attributes to the painting, namely an opulent masquerade, then presumably the owner saw it as an Orphic paradeisos, which is after all what it literally appears to represent. In which case it cannot be used to demonstrate covetous intentions other than those associated with peace and tranquillity, which is precisely what one would expect to find in a garden.

Sculpture Collections

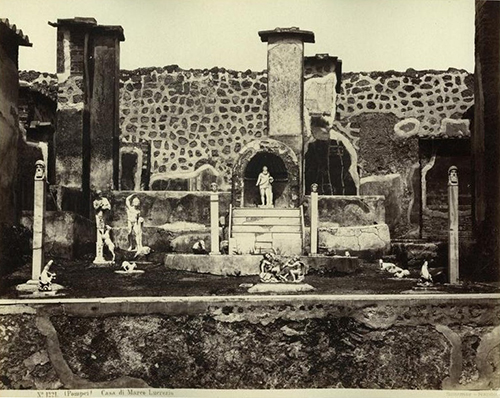

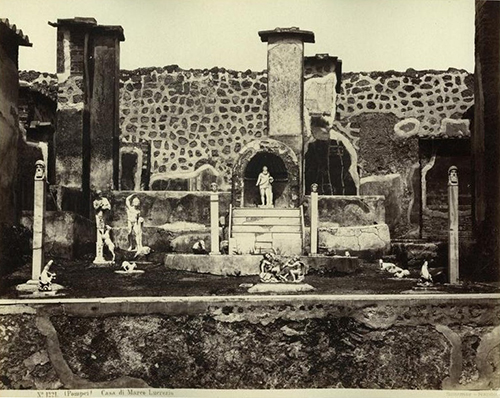

Sculptures in Pompeian gardens are also used as a way of defining the owner’s ‘taste’ and their social standing. The subsection ‘Gardens filled with Sculptures’ (pp.168-174) leaves the reader in no doubt that collections such as the one found in the garden of the House of M. Lucretius, were motivated by avarice beyond his class and status (fig.1). Most of the items are credited with little or no value, aesthetic or otherwise, other than to contribute to a ‘staged’ effect designed to impress the neighbours (p.174). Once again the Hellenistic palatial villa, this time adorned with magnificent sculptures, is offered up as the unattainable object of desire. But does it necessarily follow that if you display works of art around your house and garden that you are automatically aspiring to turn your house into a villa? The display of sculpture was after all one of the ways in which individuals and communities communicated both to themselves and to visitors.

As Pollitt points out, by the middle of the second century BC Rome had become a ‘museum of Greek art’ and was ‘inundated’ with Greek statuary as a direct result of the capture of Syracuse (211 BC) and Corinth (146 BC), as well as other sculptures taken from Tarentum (209 BC) in Magna Graecia (the Greek south of Italy). Other ancient sources, he tells us, went even further in claiming that the sack of Corinth ‘filled the whole of Italy’ with paintings and statues (Pollitt 1978:156-157). The point that is being made here is that as a result of Republican expansionist policies numerous Greek and Hellenistic works of art were located in Italy for at least 260 years prior to the late 1st Century A.D. Pompeian sculptural collections, which Zanker alludes to as being directly influenced by Hellenistic villas and their contents. Surely 260 years is enough time for the looted works to become part of the fabric of Roman society or at least absorbed and re-contextualised (fig.2). Therefore why evoke exotic foreign models, when public spaces and private Italian villas provided infinitely more accessible sources of cultural influence? The public and private sculptural collections that sprung up as a result of Rome’s successful campaigns could equally have spurred on individuals to collect and display sculpture in domestic environments. Especially since the owners of these collections did not have to imagine distant royal villas as their model, a trip to their local forum in any reasonably sized town would have provided them with all the inspiration they needed. The level to which Greek art had become part of the social fabric by the early years of the first century BC is attested to by the fact that when the Emperors who succeeded Augustus tried to reverse his policy that all Greek art should be on public display and attempted to place it back into private ownership, the people rose up and stopped them. (Pollitt 1978:167)

1

11 The critique in Pompeii - Public and Private Life, 2000 (p.174), of the sculpture collection in the garden of M. Lucretius, is based on Giorgio Sommer's late 19th Century photograph. The sculptures were removed several decades ago and we have no way of knowing if the placement of the sculptures reflected their posistion at the time of the erruption.

|